Research interests

- Ultra-faint dwarf galaxies & their dark matter content

- Stellar dynamics & dynamical friction

- Primordial black holes

- Dark matter phenomenology & interactions with stars

- Bayesian analysis; synthetic and observed stellar populations

- Strong background in theoretical particle physics

My PhD thesis research

My PhD thesis focuses on dark matter, a mysterious component of our Universe that accounts for approximately 85% of its total mass. Yet, its nature remains unknown. The presence of dark matter within galaxies was first inferred nearly a century ago through observations of stellar motion. The speed of stars in galaxies depends on the gravitational force acting upon them: the stronger the force, the faster the stars move. This gravitational force, in turn, depends on the galaxy’s mass. However, measurements revealed that the speed of stars, and thus the gravitational pull of galaxies, was greater than what could be accounted for by luminous matter alone. This discrepancy suggests that galaxies must contain an additional invisible form of matter: the dark matter.

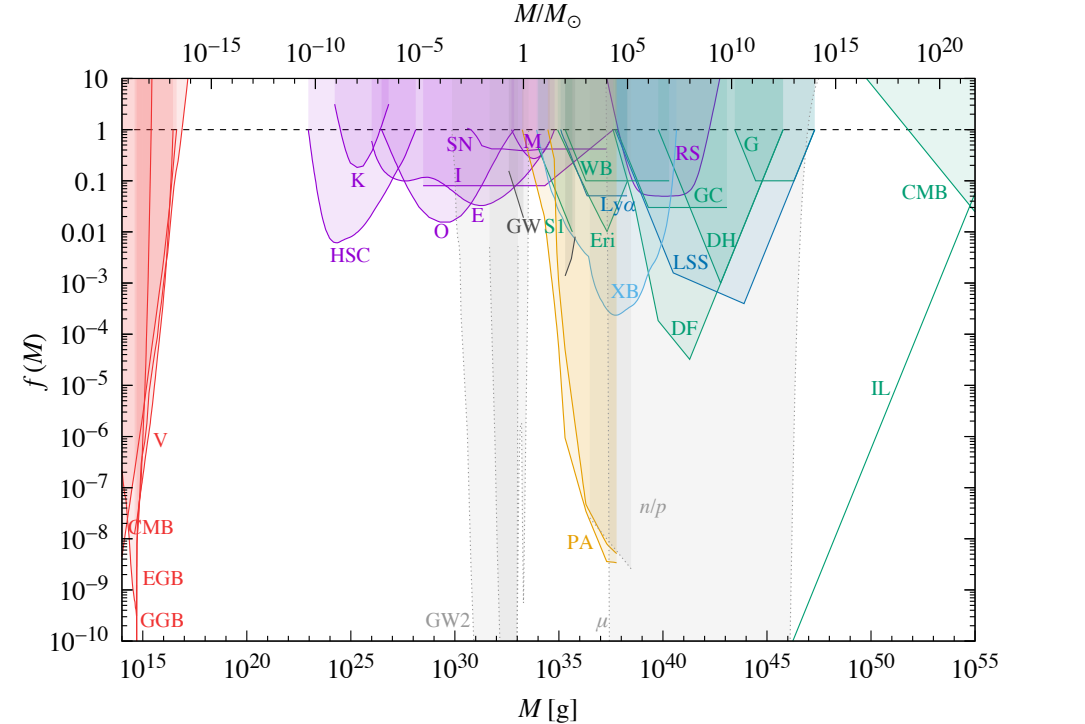

For decades, physicists have explored various theories to explain dark matter. Among the proposed candidates, primordial black holes are particularly intriguing. These theoretical black holes could have formed shortly after the Big Bang, when the Universe was extremely hot and dense, and they remain a viable possibility for constituting dark matter. My current research focuses on the phenomenology of primordial black holes; that is, the different ways they could affect the observable Universe. By studying these potential effects, we can test the model and, ultimately, advance toward identifying the true nature of dark matter, whether it consists of primordial black holes or something else entirely. The figure below shows current constraints on primordial black holes. The y-axis represents their abundance; for example, if f(M) = 1, it means that all of the dark matter is made of primordial black holes. The x-axis shows their mass, which in theory can range from a fraction of a gram to billions of times the mass of the sun. In practice, most mass ranges have been excluded through various astrophysical measurements. These excluded regions are represented as colored areas on the plot (plot taken from this paper).

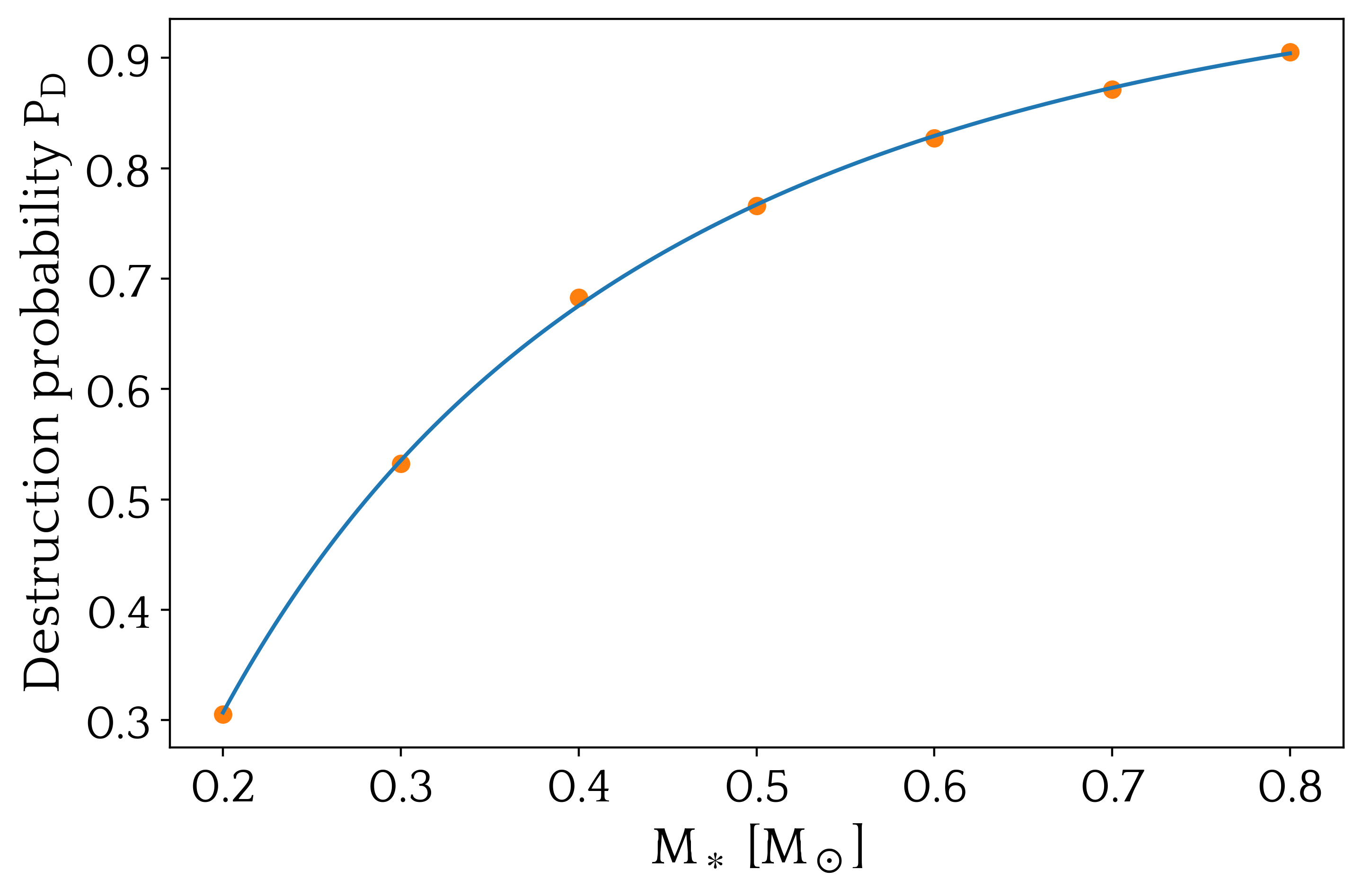

More specifically, I focus on primordial black hole whose mass would be of around 1020 grams. As you can see on the plot above, there are no constraints on the model yet in this range of masses. These black holes are very heavy, compared to human standards, but their size is microscopic! If they exist, they could interact with stars in environments where we expect a lot of dark matter to be present. Stars could capture these black holes, which would then accrete, i.e. absorb, the stellar material, and turn them into stellar mass black holes. Using theoretical arguments and calculations, I computed the probability of stars in a given environment to be accreted by primordial black holes, as shown on the following plot. It shows, on the y-axis, the probability that stars are destroyed by primordial black holes (don’t worry, this does not apply to our Sun!), plotted as a function of the stellar mass on the x-axis, expressed in units of the Sun’s mass.

Using this theoretical phenomenon, it is possible to place constraints on the primordial black hole model: if they were too abundant, they would have destroyed most stars in some very specific environments: ultra-faint dwarf galaxies. These galaxies are very small and old satellites of the Milky Way which are thought to possess large amounts of dark matter. The destruction process is dependent on the mass of the star: heavier stars are more likely to capture primordial black holes (because the capture is a gravitational process which, as explained above, is stronger with increasing mass). Therefore, heavy stars are more likely to be destroyed, as can be seen on the plot above. The box below explains what happens to stars in an ultra-faint dwarf galaxy when asteroid-mass primordial black holes are present.

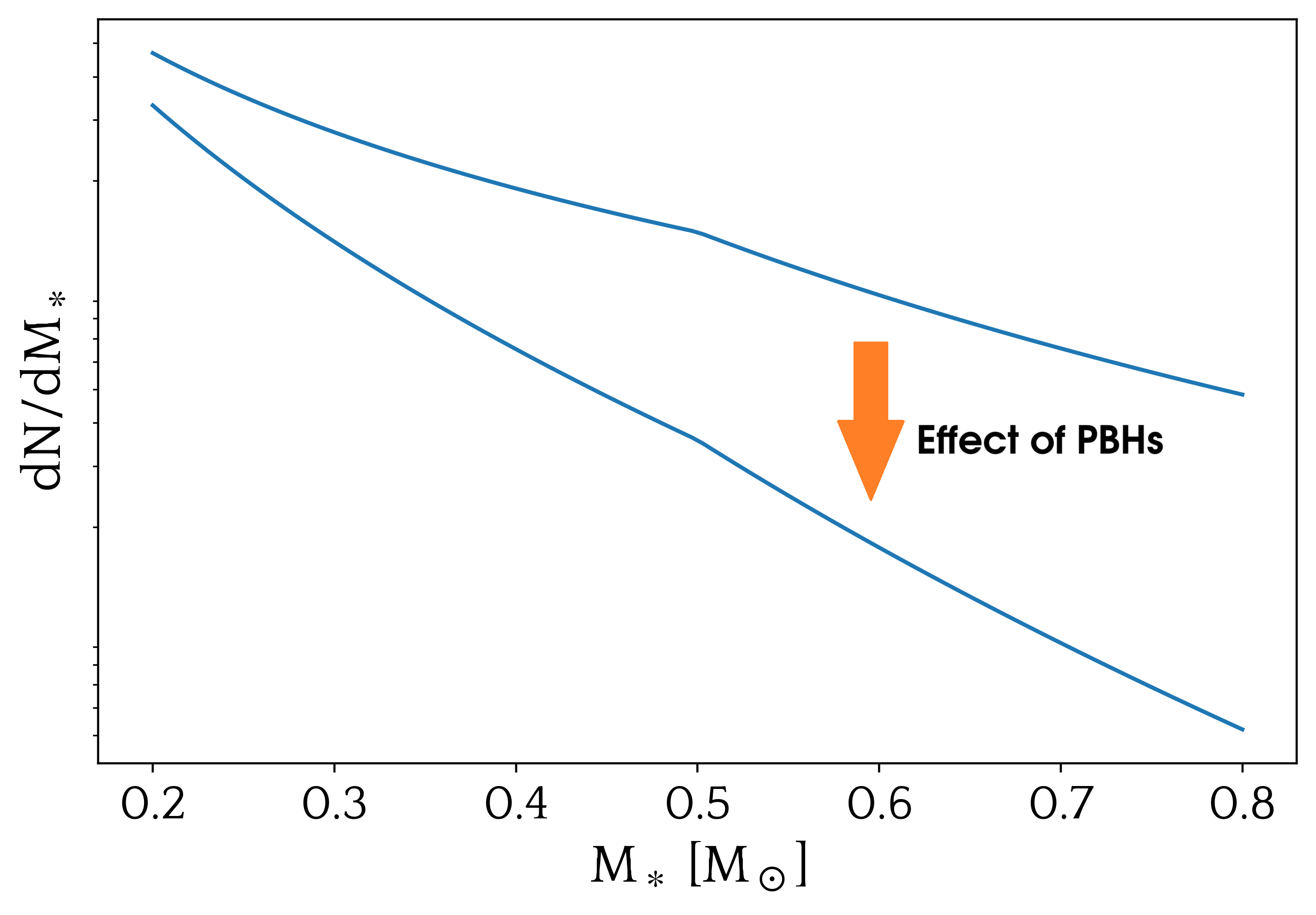

(1) From observations, we know that there are more light stars than heavy ones, as depicted on the figure below:

In the mathematical sense, the mass function of stars (i.e., the number of stars as a function of their masses, shown on the plot below) would thus evolve as follows under the effect of PBHs:

By comparing this prediction with observations, we can constrain the model: if we do not observe this predicted population with a depleted number of heavy stars, then we can say that primordial black holes should not be too abundant in ultra-faint dwarf galaxies.

More technically, I used photometric observations of three ultra-faint dwarf galaxies: Reticulum II, Segue 1, and Triangulum II, from the Hubble Space Telescope, and compared these data with predictions from my model using Bayesian analysis. I simulated stellar populations both with and without the effect of primordial black holes and compared them with the observed populations. I found no evidence for the effect of primordial black holes. Consequently, I was able to impose constraints on this dark matter model. This time it was a miss, but in the future, a similar mechanism may help us uncover the true nature of dark matter!

Other projects

Recently, I worked on a side project of my own. In this project, I study the possibility that primordial black holes, if they make up a subdominant fraction of the dark matter, may be surrounded by small dark matter clouds (also called minihalos or spikes). If this is true, then stars passing by will be slowed down by the gravitational friction due to the cloud. This may result in the creation of binary systems, with one of the members being a primordial black hole and the other a star. I then estimated the number of such binaries we should see, either in the form of X-ray binaries in the Milky Way, or as gravitational wave events if the stars collapse into compact objects and then later on merge with the black holes they pair with. I found that these could yield non-negligible rates for both types of events. Therefore, if the Universe comprises primordial black holes surrounded by dark matter clouds, we may someday observe one of these binaries!